January 2023

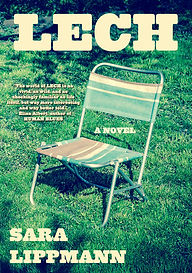

Lech

by Sara Lippmann

Tortise Press, 298 pp.

Reviewed by Janice Weizman

Some books are like snapshots — vivid reproductions of a particular moment with all that their subjects carry — legacies, inheritances, vestiges of lost pasts, as well as a hopeful open-endedness that characterizes works in progress. Lech, a debut novel by Sara Lippmann (who has authored two story collections) is that sort of book. The novel deals with a motley collection of characters over the summer of 2014, who live, whether permanently or temporarily or uncertainly, around Sullivan County, on the shores of Lake Murmur in the Berkshires. Here’s how Lippman describes the region in the book’s prologue:

“Industry has been lost. Seasons turn. Road signs wage a battle of red over blue, the color of blood outside or in, and it’s unclear what is won by winning…Farms lie fallow and for sale. Religion ransacks the fitful heart. What’s left are gun shops, a broken roof, the faint smell of stretched hide from centuries-old tanneries, long closed.”

It’s a setting in which nothing much is expected to happen, and in terms of the book’s plot, nothing much does. Rather, a reader might come to this book for the skillfully crafted portrayals of character that expertly convey the emotional landscape of their subjects. Here, for example is Lippman depicting 66-year-old Ira Lecher (the book’s title, Lech, is his nickname, and yes, the Hebrew biblical allusions are there on purpose) watching his new tenants, Beth and her 4 year-old son Zach, as they arrive at the lakeside property he has rented out to them for the season.

“She has a child. The good ones always do. Ira remains confounded by his own adult children, Heather and Hillary. He’s nothing got do with them. Kids complicated matters. Kids came between perfectly decent people, but this kid—honey curls, bare feet—Ira understands implicitly: the boy speaks his language of want. He wants to be put down, but she whisks him up and over to the tall field by the side of the house adjacent to the outdoor shower he built, a simple pine box, akin to what he buried his parents in, door with a rusted hinge. The boy sneezes. Mom stops, drops, peers up the kid’s nose as if it contained all the world’s answers, at which point he breaks free, falling back on the lawn as if onto a mosh pit, as if life were a trust game on which to be buoyed by infinite cheering hands. As if. The kid beetles the air. Uproots a fistful of dandelions whose fluff he casts with profligate, reckless abandon A ribbon of dust sails behind him. How the world speaks to the young. Ira feels it in the kishkes: To have one’s whole life ahead!”

The passage is indicative of the way Lech unfolds, its lasar sharp gaze focused on individual moments that characterize the full personality, here highlighting Ira’s instinct for poignancy and nostalgia—traits which often overtake and define him. But no overiding story is to be found in the novel. Instead, there are a series of small trajectories: that of Noreen Murphy, a scrappy, aging real estate agent who is trying to engineer a sale of her neighbors’ properties, of her daughter Paige, dealing in drugs stolen from the hospital where she works and dreaming of moving to Florida, of Beth – running away from her life in the city as she recovers from an abortion. There is also Tzvi – a young Satmer Hasid, semi-estranged from his community, and one of Paige’s clients.

Tzvi, and the local Haredi community, always seems to be in the background of what is going on, whether they are bowling at the local alley, running Camp Shalom Yisroel, or hanging out at the Sullivan County fair. In Lech, they form one end of a spectrum of Jewish identity and existence on offer. At the other is the lingering memory of the famous Borsht-belt country clubs where Jews once vacationed. Though the clubs and their patrons are long gone, they retain a powerful grip on Ira’s subconscious. In a dreamlike state, Ira envisions visiting the place, “a ghost of its former self, given over to graffiti and weeds,” as he explores the grounds with Beth:

“They trespass through the criminal tangle of abandonment, a rusted band of wire, syringe, bottle and excrement, animal or human he can’t be sure, got to watch where you walk, the grass so tall it scaffolds his knees, scything their way through the rotted grandeur and up the everlasting hill. The pool is an Olympic grave of chairs, vellum, oceanic drapes, pillows bursting and the seams…It’s like staring into a memorial pit until Beth latches on to his elbows, like his parents steered him to shul on the rare Shabbos his father was not on the road, careful not to get their heels caught in the concrete, cobblers do not come cheap, my son.”

Shul, and Shabbos, are ghost words here, remnants of a heritage Lech has long left behind. Likewise, Beth may send Zack to Camp Shalom Yisroel, but she has little Jewish affiliation. Judaism here is signpost, a past willingly abandoned.

The descriptions on the back cover of the book frame the overriding theme as a “timeless question: How do we carry on?” The answer, it would seem, is to be found in Lippmann’s exquisite writing, which focuses our attention on the small details that tell a larger story, not only about the individuals that inhabit the dreary towns of upstate New York, but also about the forces that have left them to their fate. It’s a bleak, disheartening vision, in many ways a portrait of failure, but as the ideals and aspirations once epitomised by the patrons of the Borsht Belt country clubs go down the tubes, we can take comfort in the power of expert prose to depict even our own times in truth, and a sort of beauty.